A Hegemon over Southeast Asia? The Rise and Fall of Vietnamese Ambition

Abstract

This article traces the rise and collapse of Vietnam’s expansionist and hegemonic ambitions between 1975 and 1991. Following its victory in the Vietnam War, Hanoi emerged as Southeast Asia’s most powerful military actor. Backed by the Soviet Union, Vietnam projected power outward, subjugating Laos, invading Cambodia, and challenging Thailand’s sovereignty. This expansionist phase reflected both local strategic imperatives and the enabling conditions of Cold War bipolarity. However, Vietnam’s ambitions proved unsustainable. The economic burden of the war in Cambodia and the hostility of its neighbors imposed growing costs. Most crucially, the shift from the Cold War bipolarity to the U.S. ‘unipolar moment’ and the collapse of the Soviet Union deprived Hanoi of its sole great power patron, undermining the material foundation of its hegemonic project. By the early 1990s, Vietnam had withdrawn from Laos and Cambodia and shifted its focus toward regional reintegration and economic reform. The article argues that Vietnam’s trajectory confirms a key insight of neorealist theory: the international system’s structure and the presence or absence of great power backing condition the viability of minor powers’ expansionist behavior. Without bipolarity and Soviet support, Vietnam’s ambitions unraveled. The study contributes to broader debates on the structural constraints shaping the behavior of revisionist states.

Tags: Cambodian-Vietnamese War, neorealism, Soviet Union, Southeast Asia, territorial expansion, Vietnamese foreign policy

Dylan Motin (Seoul National University)

Note: This article is based on Chapter 6 of my Territorial Expansion and Great Power Behavior during the Cold War: A Theory of Armed Emergence (Routledge, 2025).

Between 1975 and 1991, Vietnam transformed from Southeast Asia’s main expansionist and revisionist power to a quietly status quo-accepting state. After its victory over the United States in 1973 and the fall of Saigon in 1975, a newly unified Vietnam emerged as the dominant military force in Southeast Asia. Emboldened by Soviet power, Hanoi pursued an aggressive policy of expansion, hoping to translate its military strength into territorial conquest and regional hegemony. Why did Vietnam turn from a threatening juggernaut in the 1970s and 1980s to a status quoist power since the 1990s?

In this piece, I argue that Vietnam’s expansionist ambitions ultimately collapsed due to the shift in global polarity at the end of the Cold War. The decline and eventual collapse of the Soviet Union deprived Vietnam of its sole great power patron, forcing Hanoi to retreat from its expansionist tendencies and embrace a policy of regional reconciliation. This article explicates the rise and fall of Vietnamese ambition from 1975 to 1991, arguing that the shift in global great power structure — specifically, the end of bipolarity and the emergence of U.S. unipolarity — was the decisive factor that ended Vietnam’s hegemonic project.

Vietnam Ascendant after 1975

The end of the Vietnam War in 1975 radically altered the balance of power in Southeast Asia. North Vietnam’s conquest of the South created a unified and battle-hardened state equipped with Southeast Asia’s largest and most capable military. By 1980, Vietnam had a standing army of over one million troops, commanding more combat potential than all of ASEAN combined (Pike, 1981: 87). It also benefited from massive Soviet arms transfers and political support. Demographically, Vietnam had surpassed Thailand, adding to its military strength a superiority in population over its neighbors.

Vietnam’s strategic geographic location encouraged it to look westward. After 1975, Vietnamese leaders sought political domination across the region, particularly through close integration with Laos and Cambodia. With Laos under Vietnamese influence and Cambodia soon to follow, Vietnam could dream of controlling Southeast Asia’s core. This region, basically the Mekong River valley, is rich in fertile soil and amply populated. Commandeering it would grant Hanoi access to substantial resources, bolstering its power and making it more formidable. In addition, controlling the area would constitute a buffer zone against Chinese pressure.

Unsurprisingly, neighbors were terrified of Vietnam’s power and ambitions. Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew feared that “no combination of forces in Southeast Asia […] can stop the Vietnamese on the mainland of Asia” (quoted in Emmers, 2005: 648). China’s Deng Xiaoping warned that the coming “Indochinese Federation is to include more than three states […] The three states is only the first step. Then Thailand is to be included” (quoted in Kissinger, 2011: 364).

The Expansionist Phase: Vietnam’s Expansionist Bid, 1975–1985

Vietnam’s ambition first manifested itself in Laos, where the Pathet Lao established a communist regime under Vietnamese tutelage in December 1975. Hanoi quickly consolidated its position, stationing tens of thousands of troops and effectively managing the Laotian government from behind the scenes (Brown and Zasloff, 1986: 245–246; Stuart-Fox, 1980: 204). Laos became a forward base for projecting Vietnamese influence into Thailand and supporting Thai communist insurgents (Morris, 1999: 96–97). In 1977, Hanoi signed a 25-year Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with Vientiane, formalizing a strategic alliance and deepening Vietnam’s control. Vietnamese troops remained in Laos in clear violation of the 1973 Paris Peace Accords. Furthermore, Hanoi settled Vietnamese civilians, party cadres, and police personnel in Laos, entrenching its influence throughout Laotian society and institutions (McBeth, 1979).

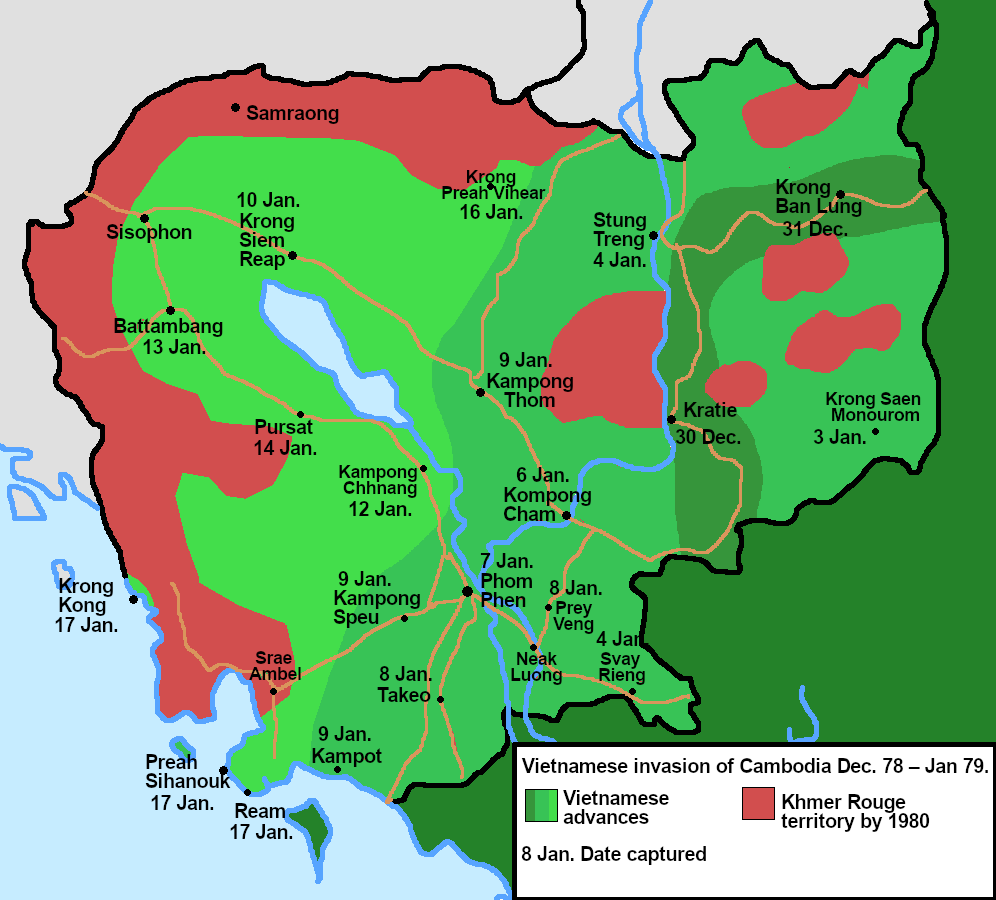

Cambodia became the centerpiece of Hanoi’s ambitions. It was a large country and key to the security of Vietnam’s southern half. The Khmer Rouge regime, deeply antagonistic toward Vietnam and aligned with China, clashed regularly with Vietnamese border forces. In response, and with Soviet backing, Vietnam launched a full-scale invasion on 25 December 1978. By early January 1979, the Vietnamese army had toppled Pol Pot and installed the pro-Hanoi People’s Republic of Kampuchea (Morris, 1999: 105–106). The conquest of Cambodia was far-reaching. Vietnamese officials oversaw nearly all levels of administration, military planning, and economic restructuring in Phnom Penh (Clayton, 2000: 114–115). Tens of thousands of Vietnamese settlers and technicians were deployed to Cambodia to assist in governance and ensure compliance. Vietnamese troops remained in large numbers, fighting a protracted insurgency by the Khmer Rouge and other resistance groups.

Vietnamese ambitions even extended to Thailand. Hanoi’s long-standing support for the Communist Party of Thailand intensified through Laos, which served as a staging ground. When the Communist Party of Thailand eventually sided with China against Vietnam, Hanoi established a new proxy force, the Pak Mai, to replace it in 1980, based in Vientiane and under Vietnamese supervision (Kim, 1983: 52; Weatherbee, 1983: 113). Repeated Vietnamese incursions into Thai territory throughout the 1980s — ostensibly to chase Khmer Rouge rebels — further inflamed tensions. Vietnamese shelling of Thai border villages and brief occupations of frontier posts convinced Bangkok that Hanoi harbored ambitions toward Thailand. Naturally, Thai strategists viewed a Vietnamese-dominated Indochinese bloc as a grave threat to their own security and regional equilibrium (Raymond, 2020: 18).

The Importance of Soviet Endorsement

Vietnam’s expansionist behavior was possible only because of Soviet support. The USSR viewed Vietnam as a key partner to counter-flank China and expand its influence in Southeast Asia. Soviet advisors were deeply embedded in Vietnam’s economic and military structures, and the Kremlin provided billions in aid, weaponry, and diplomatic cover for Vietnam’s occupation of Cambodia (Morris, 1999: 212; Simon, 1979: 197–198, 221; Stuart-Fox, 1980: 204–205).

In November 1978, just weeks before the Cambodian invasion, Vietnam and the USSR signed a Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, creating a de facto alliance. Soviet military deliveries peaked in late 1978, and the USSR began using the Cam Ranh Bay naval base shortly thereafter. Soviet air and naval forces stationed in Vietnam served to deter Chinese intervention and enabled Hanoi to focus on its expansionist campaign.

In contrast, China perceived Vietnam’s hegemonic drive as a grave threat. Beijing had supported the Khmer Rouge and saw Vietnamese actions as part of a Soviet attempt to encircle China. In response, Beijing invaded northern Vietnam in early 1979, inflicting damage but failing to force Hanoi out of Cambodia. China also backed the Khmer Rouge insurgency and supported Thailand, while mounting a broader diplomatic campaign against Vietnam. Despite these efforts, Soviet economic and military aid gave Hanoi the wherewithal to maintain its course through most of the 1980s. Hence, Vietnam’s hegemonic ambition remained precariously dependent on external support.

The Collapse of Soviet Power and the End of Expansion

Despite its battlefield victories, Vietnam’s expansionism proved unsustainable. The occupation of Cambodia drained the Vietnamese economy, with tens of thousands of troops tied down in counterinsurgency and occupation efforts (Simon, 1979: 221). The cost of maintaining control over Indochina amounted to nearly a third of Vietnam’s GDP in some years, crippling domestic development (Pike, 1981: 87).

Thailand and ASEAN rallied diplomatically and militarily, turning Southeast Asia against Hanoi’s rising clout. Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia all condemned Vietnamese behavior, fearing that their own sovereignty could be at risk. Bangkok became a hub for anti-Vietnamese activity, and Thailand received U.S. military assistance and intelligence to counter Hanoi’s influence. The Khmer Rouge, despite its atrocities, gained international sympathy as a symbol of anti-Vietnamese resistance. The United States encouraged China and ASEAN countries to covertly aid its fighters along the Thai-Cambodian border. Vietnamese troops were drawn into a costly and prolonged guerrilla war that drained resources and demoralized their forces. Vietnam’s domestic economy was another constraint. Already under strain from war, Hanoi now had to feed and stabilize a hostile Cambodia while dealing with internal shortages. The Khmer Rouge’s scorched-earth tactics in their retreat forced Vietnam (and the Soviet Union behind it) to subsidize vast portions of Cambodian life, placing even greater pressure on a faltering economy (Simon, 1979: 221).

What finally ended Vietnam’s hegemonic project was not battlefield defeat but the collapse of bipolarity. The Soviet Union’s gradual disengagement, beginning with Gorbachev’s “new thinking” in the mid-1980s, signaled that Moscow was no longer willing or able to subsidize Hanoi’s ambitions (Williams, 1991). Soviet aid decreased dramatically, and with the USSR’s implosion in 1991, Vietnam lost its only great power sponsor.

This left Hanoi dangerously exposed. China remained hostile, the United States was ascendant, and ASEAN had begun integrating into a more cohesive bloc. Without Soviet protection and funding, the costs of occupation became intolerable. Vietnamese troops withdrew from Laos in 1987–1988 and began withdrawing from Cambodia in 1989. The 1991 Paris Peace Agreements marked the formal end of Vietnam’s occupation.

Shorn of its great power backer and surrounded by increasingly powerful neighbors, Vietnam recalibrated its approach. It joined ASEAN in 1995 and adopted a more modest, status quo-oriented foreign policy. The dream of an Indochinese Federation gave way to economic reform and diplomatic engagement (Emmers, 2005: 648–649). Thai economic resurgence and Vietnamese exhaustion ensured a reversal of roles: Vietnam would play catch-up, while Thailand became the political and economic engine of mainland Southeast Asia.

Great Power Structure and Minor Power Behavior

Vietnam’s rise and fall as an expansionist power and would-be hegemon in Southeast Asia confirms a core tenet of neorealist theory (Waltz, 1979): the structure of the international system heavily determines the viability of minor power expansion. Between 1975 and 1985, Soviet backing provided Hanoi with the material and diplomatic resources necessary to pursue its expansionist goals. But when the great power polarity changed, with the USSR weakening and ultimately disappearing, Vietnam could no longer afford or sustain its regional ambitions.

Vietnam’s experience illustrates how ambitious minor powers can become predatory states under the right structural conditions. But once those conditions vanish, even the most aggressive and capable regional powers must retreat. Today, Vietnam’s more restrained foreign policy is not simply the result of historical learning or ideological moderation but of structural necessity. The loss of the Soviet Union, its sole great power support, forced Hanoi to abandon empire and embrace the regional status quo. In the end, it was the transformation of the global order and the advent of the U.S.-led unipolar world that ended Vietnam’s bid for regional domination.

저자 소개

딜런 모틴Dylan Mortin(dylanmotin@snu.ac.kr)은

서울대학교 아시아연구소 방문학자이자 퍼시픽포럼(Pacific Forum)의 켈리비상임연구원이다. 터너컨설팅(Terner Consulting) 소속 전문가이자 한국핵안보전략포럼 비상임 펠로우도 겸임하고 있다. 저서로는 Territorial Expansion and Great Power Behavior during the Cold War: A Theory of Armed Emergence (Routledge, 2025), How Louis XIV Survived His Hegemonic Bid: The Lessons of the Sun King’s War Termination (Anthem Press, 2025), and Bandwagoning in International Relations: China, Russia, and Their Neighbors (Vernon Press, 2024) 등이 있다.

Dylan Motin (dylanmotin@snu.ac.kr)

is a Visiting Scholar at the Seoul National University Asia Center and Non-resident Kelly Fellow at the Pacific Forum. He is also an Expert at Terner Consulting and a Non-resident Fellow at the ROK Forum for Nuclear Strategy. He is the author of Territorial Expansion and Great Power Behavior during the Cold War: A Theory of Armed Emergence (Routledge, 2025), How Louis XIV Survived His Hegemonic Bid: The Lessons of the Sun King’s War Termination (Anthem Press, 2025), and Bandwagoning in International Relations: China, Russia, and Their Neighbors (Vernon Press, 2024).

References

Brown, MacAlister, and Joseph J. Zasloff. 1986. Apprentice Revolutionaries: The Communist Movement in Laos, 1930–1985. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press.

Clayton, Thomas. 2000. “The Shape of Hegemony: Vietnam in Cambodia, 1979–1989.” Education and Society, 18 (2): 109–124. https://doi.org/10.7459/es/18.2.08.

Emmers, Ralf. 2005. “Regional Hegemonies and the Exercise of Power in Southeast Asia: A Study of Indonesia and Vietnam.” Asian Survey, 45 (4): 645–665. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2005.45.4.645.

Kim, Shee Poon. 1983. “Insurgency in Southeast Asia.” Problems of Communism, 32 (3): 45–55.

Kissinger, Henry. 2011. On China. New York: Allen Lane.

McBeth, John. 1979. “Laos: The Government under Guard.” Far Eastern Economic Review, 105 (34): 10–11.

Morris, Stephen J. 1999. Why Vietnam Invaded Cambodia: Political Culture and the Causes of War. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Pike, Douglas. 1981. “Vietnam in 1980: The Gathering Storm?” Asian Survey, 21 (1): 84–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/2643667.

Raymond, Gregory V. 2020. “Strategic Culture and Thailand’s Response to Vietnam’s Occupation of Cambodia, 1979–1989: A Cold War Epilogue.” Journal of Cold War Studies, 22 (1): 4–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/jcws_a_00924.

Simon, Sheldon W. 1979. “Kampuchea: Vietnam’s ‘Vietnam.’” Current History, 77 (452): 197–198, 221–223. https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.1979.77.452.197.

Stuart-Fox, Martin. 1980. “Laos: The Vietnamese Connection.” Southeast Asian Affairs, 7: 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1355/9789812306708-013.

Waltz, Kenneth N. 1979. Theory of International Politics. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Weatherbee, Donald E. 1983. “Communist Revolutionary Violence in the ASEAN States: An Assessment of Current Strength and Strategies.” Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 1 (3): 109–120.

Williams, Michael C. 1991. “New Soviet Policy toward Southeast Asia: Reorientation and Change.” Asian Survey, 31 (4): 364–377. https://doi.org/10.2307/2645390.