지속적인 환경 문제

2025년 4월 21일 선종한 프란치스코 교황은 필리핀에서 매우 존경받는 인물로, 앞으로도 오랫동안 기억될 것이다. 이는 2015년 1월, 열대성 폭풍 메칼라(필리핀명 아망)의 접근으로 인해 방문을 취소하라는 권고를 받았음에도 불구하고, 레이테 주 타클로반에서 미사를 집전했던 것이다. 이 미사는 2013년 슈퍼 태풍 하이얀(필리핀명 욜란다)으로 희생된 약 6,000명의 영혼을 기리기 위해 봉헌된 것이었다.

이 사례는 필리핀 사회가 태풍과 열대성 폭풍으로부터 얼마나 큰 영향을 받고 있는지를 단적으로 보여준다. German Watch에 따르면, 1993년부터 2022년까지 총 372건의 극한 기상 현상으로 필리핀은 인플레이션을 반영한 약 340억 달러의 피해를 입었으며, 극한 기상 현상의 영향을 가장 많이 받는 국가 순위에서 10위를 기록했다(German Watch, 2025). 상위 4개국은 도미니카공화국, 중국, 온두라스, 미얀마이다. 이러한 극한 기상 현상에는 가뭄, 홍수, 폭염, 폭풍, 산불 등이 포함된다.

German Watch는 또한 IPCC 제6차 평가보고서를 인용하여 “3~5등급에 해당하는 열대성 저기압(태풍)의 발생 비율과 ‘급속 강화’ 현상의 빈도가 지난 40년간 전 세계적으로 증가했을 가능성이 높다”고 밝혔다. 이는 기후 변화로 인해 바람이 더 강해지고, 해수면 온도와 대기 온도가 상승하면서 공기 중 수증기량이 증가해 폭우가 빈번해지는 등, 태풍의 위력과 발생 빈도가 모두 커지고 있다는 점을 시사한다.

이 글은 동남아시아에서 인도네시아에 이어 두 번째로 인구가 많은 국가인 필리핀의 해안 지역 생계에 초점을 맞춘다. 인도네시아의 인구는 약 2억 8,400만 명, 필리핀은 약 1억 1,400만 명이며, 필리핀 인구의 약 60%는 저지대 해안 지역에 거주하고 있다. 이들 해안 지역 사회는 태풍과 폭풍 외에도 홍수, 염수 침투, 해안 침식, 해수면 상승, 과도한 어업, 그리고 도시 지역에서는 토양 침하(마닐라, 자카르타, 방콕, 호찌민 등 동남아 대도시에서 공통적으로 나타나는 현상) 등 다양한 위협에 노출되어 있다(Stockholm Environment Institute, 2024).

필자는 2014년부터 필리핀 해안 지역 사회를 대상으로 현지 조사를 수행해 왔으며, 특히 어민과 해초 양식업자들이 환경 문제에 어떻게 대응하고 적응하는지, 그리고 관련 정책이 어떻게 하면 보다 효과적으로 작동할 수 있는지에 대한 연구를 진행해 왔다. 본 글에서는 그간의 연구를 통해 확인한 사실들과 함께, 정책 및 실천 차원에서 고려할 수 있는 가능한 대응 방안을 제시하고자 한다. 첫 번째 사례는 팔라완 주의 해초 양식업자와 관련된 것이며, 두 번째 사례는 일로일로 주의 어민 공동체에 관한 것이다.

팔라완의 해초 양식업자들

필리핀의 해안 지역에는 여전히 수천 가구가 카라기난 해초—특히 Kappaphycus alvarezii—재배에 부분적으로 생계를 의존한다. 이 해초는 식품, 화장품, 의약품에 사용되는 증점제 및 결합제인 카라기난으로 정제되며, 필리핀은 인도네시아에 이어 세계에서 두 번째로 큰 카라기난 해초 생산국이며, 중국에 이어 두 번째로 많은 카라기난 수출국이다.

2013년부터 2022년까지 카라기난 수출의 연평균 가치는 약 2억 700만 달러에 달하며, 이는 필리핀 수산물 중 참치에 이어 두 번째로 높은 수출 가치를 기록한 품목이다. 인도네시아는 세계 최대 해초 생산국이지만, 정제 역량이 부족하여 대부분의 해초를 중국 정제 공장으로 수출하고 있다. 반면 필리핀은 비교적 잘 조직된 해초 가치 사슬을 보유하고 있으며, 국내적으로도 상당한 정제 능력을 갖추고 있다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 해초 재배에 의존하는 다수의 가구는 여전히 빈곤과 사회경제적·환경적 취약성에서 벗어나지 못하고 있다. 실제로 해초 양식이 이루어지는 해안 지역 사회는 필리핀 내에서 가장 가난한 계층 중 하나에 속한다.

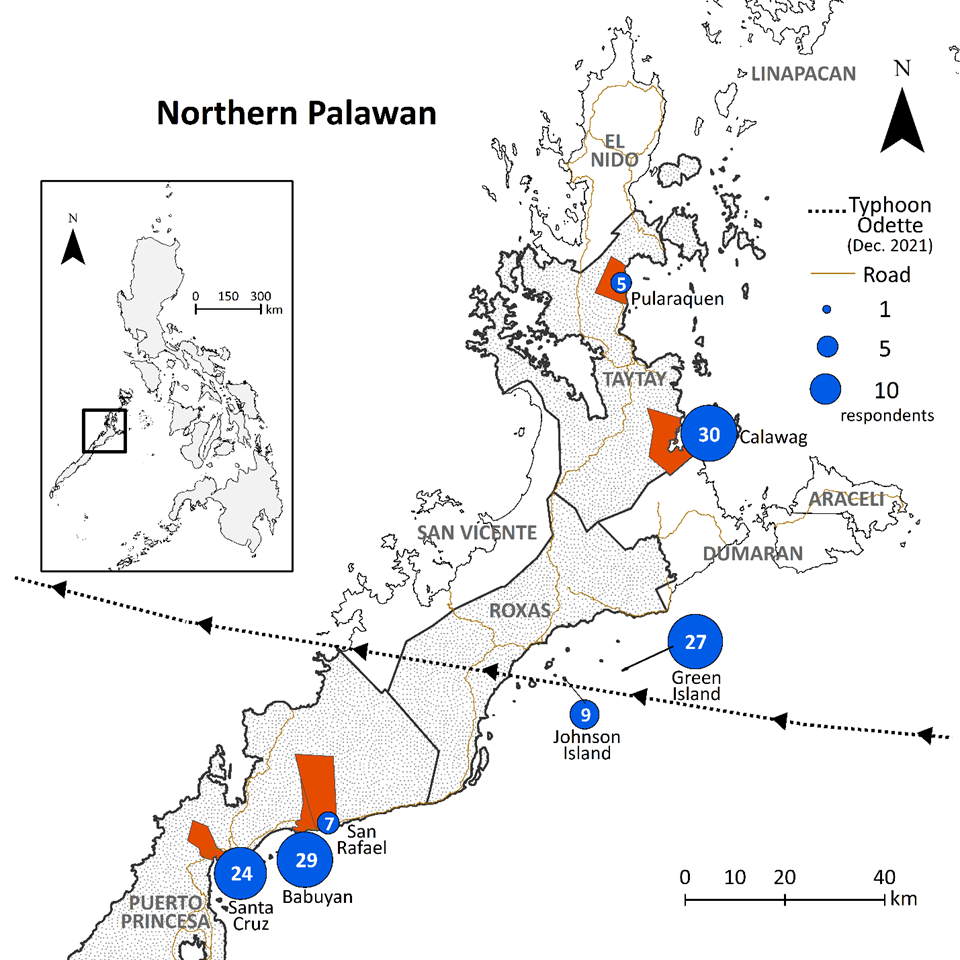

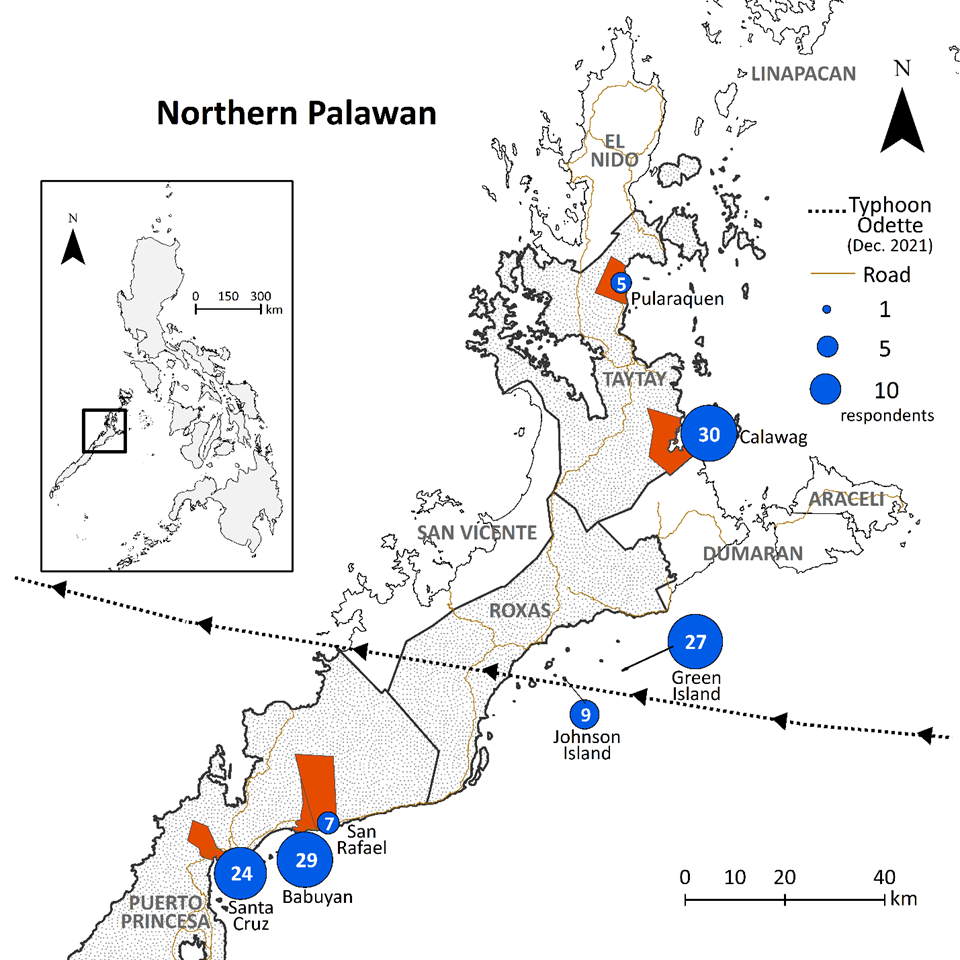

필자는 팔라완주립대하교 연구팀과 함께 팔라완 섬 북부 지역에 위치한 7개 마을에서 해초 양식 가구의 생계 변화에 대한 조사를 실시하였다. 팔라완은 해초 양식의 오랜 전통을 지닌 지역으로, 2000년부터 2011년까지 해초 생산량이 꾸준히 증가하면서 수백 가구의 소득이 증대되었고, 어업에 대한 의존도도 줄어들었다. 그러나 2011년 이후 생산량은 점차 감소하기 시작했다. 최근에는 코로나19 팬데믹과 2021년 12월 발생한 슈퍼 태풍 라이(필리핀명 오데트)가 해초 산업 회복에 큰 걸림돌로 작용하고 있다. 아시아개발은행(ADB)은 초강력 태풍이 국가 전체의 경제 활동을 약 3% 감소시킬 수 있다고 추정한 바 있으며, 과거 자료에 따르면 1990년부터 2020년까지 필리핀은 태풍으로 약 200억 달러의 경제적 손실을 입은 것으로 나타났다. 예컨대, 2024년 발생한 태풍 크리스틴은 필리핀 농업 부문에 약 62억 페소의 피해를 입힌 것으로 추산된다(Department of Science and Technology. 2024).

출처: 저자 제공

출처: 배광원

최근 해초 생산량이 다소 회복세를 보이고 있으나, 2008년부터 2011년까지의 황금기 수준으로 회복될 수 있을지는 여전히 불확실하다. 본 조사는 두 가지 핵심 질문에 초점을 맞추었다. 첫째, 왜 안정적인 생산량 유지는 지속적으로 어려운 과제가 되었는가? 둘째, 해초 재배 가구는 반복되는 위기 속에서 어떻게 생계를 이어가고 있는가? 2024년에 실시한 138가구 대상 설문조사와, 2017년 및 2024년에 진행한 반구조화 인터뷰 결과에 따르면, 해초 재배 가구는 생활 수준을 안정적으로 향상시키기보다는 여전히 생계 불안정에 시달리고 있는 것으로 나타났다(Andriesse and Lee, 2021).

태풍의 여파를 포함한 환경적 문제 외에도, 각 가정은 불안정한 지역 정치 환경 속에서 생존 전략을 모색해야 한다. 다음의 두 인용문은 지역 권력 구조와 금융 자원의 관계가 실질적으로 어떤 영향을 미치는지를 단적으로 보여준다.

“중개인에게 대출을 받고 있기 때문에 협회를 통한 통합은 어려울 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 한 재배자는 방카(양 옆에 부착된 아웃리거가 있는 전통 카누) 한 대를 구매하기 위해 2만 페소를 빌렸고, 대출자는 10개월 이내에 원금과 이자를 모두 상환하라고 요구했습니다. 또한, 구매자가 해초 가격을 미리 정해놓고 현금 선급금을 지불하는 경우도 있습니다.”

(2024년 1월 18일, 바랑가이 바부얀 주요 정보원 인터뷰)

“저는 대출업자이기도 합니다. 작년에 사무직을 그만두면서 이 일을 시작했습니다. 요즘은 30명의 해초 재배업자가 저에게서 돈을 빌리고 있습니다. 우리 사이에는 서면 계약이 없습니다. 어떤 이들은 5,000페소를, 어떤 이들은 15,000페소까지 빌려 갑니다.”

(2024년 1월 21일, 해초 협회 회장 인터뷰)

설문조사와 인터뷰 결과는 다음과 같은 복합적인 어려움을 드러낸다. 단기적인 태풍 경보 체계, 슈퍼 태풍 라이의 여파, 해초 생산량을 줄이는 ‘빙빙병’, 해조류를 섭취하는 바다거북, 고품질 모종 부족 및 가격 변동, 그리고 지역 권력 역학이 그것이다. 이러한 요인들로 인해 빈곤에서 영구적으로 벗어나기란 여전히 어려우며, 해안 지역에서는 취약성이 더욱 심화되고 있다. 기후변화의 영향이나 가격 변동과 같은 국제적 요인뿐 아니라, 국가 및 지역 수준의 구조적 문제도 생계 안정에 큰 장애물로 작용하고 있다. 이처럼 공간적으로 얽힌 복합 요인들은 팔라완 해초 양식업자들이 생계 기반을 안정적으로 다변화하기 어렵게 만든다.

2017년부터 2024년까지 다양한 생계 다각화 시도가 있었으나(직조, 바닷가재 양식 등), 대부분은 지속되지 못하고 위축되었다. 관련 단체들은 구조적 변화를 이끌 만큼 충분히 강력하지 않았다. 결국 어업으로의 회귀와 타 지역 또는 해외로의 이주가 가장 주요한 대응 전략이 되었으며, 이는 필리핀의 해양 생태계와 도시 노동시장에 더 큰 부담을 주고 있다.

결론적으로, 이 연구는 상류 글로벌 가치사슬과 연계된 생계 구조를 면밀히 분석하는 것이 필수적임을 보여준다. 필리핀의 카라기난 수출은 비교적 안정적인 주요 해양 최종산물이지만, 그것에 의존하는 수천 명의 해조류 양식업자와의 사회경제적 간극은 여전히 심각하다. 따라서 필리핀 해안 지역의 생계는 환경적 위협과 제도적 한계로 인해 지속적으로 불안정하고 취약한 상태에 놓여 있다.

일로일로의 어부들

북부 팔라완 외에도, 필자는 서부 비사야로 불리는 지역에 위치한 일로일로 주에서도 여러 차례 현지 조사를 수행하였다. 2018년에는 일로일로 적십자사 소속 자원봉사자와 연구 보조원, 그리고 필자가 함께 3개 지자체의 11개 해안 마을에서 313명의 소규모 어부를 대상으로 조사를 진행하였다(Andriesse, 2020). 2023년에는 바로탁 비에호(Barotac Viejo)의 두 마을에서 동일한 방식으로 50명의 소규모 어부를 대상으로 조사를 실시하였다. 이 중 상당수는 2018년에 이미 대화를 나눈 이들로, 조사는 종단적 분석의 기회를 제공하였다. 향후 이 50명의 어부와 그 가족을 장기적으로 추적하고자 하며, 그들의 자녀가 수십 년 내 중산층에 진입할 수 있을지, 또 그들의 생계 및 거주의 지리적 양상이 어떻게 변화할지를 관찰하고자 한다.

현지 조사를 바탕으로, 환경 문제가 지속되고 있으며 빈곤 감소는 매우 장기적인 과제라는 점, 그리고 소규모 어업이 소득 증대로 이어지지 않는다는 사실이 분명해졌다. 조사 결과, 세 가지 환경적 요인과 두 가지 정치경제적 장애 요인이 확인되었다.

첫 번째 환경 문제는 빈번한 태풍에 대한 적응이다. 바로탁 비에호 주민들은 2013년 11월 7–17일의 슈퍼 태풍 라이(오데트), 2022년 10월 28~30일의 강력한 열대성 폭풍 날개(팽) 등 다양한 폭풍의 피해를 경험하였다. 이로 인해 주택과 어선이 파손되어 재건이 필요했으며, 이러한 피해는 지역의 지속적 사회경제 발전을 심각하게 저해하였다. 해안 복구를 위한 맹그로브 식재나 해초 재배 다각화 등은 새로운 시도이지만, 태풍이 해당 지역을 강타할 경우 재정적 자원이 낭비될 위험이 있다. 실제로 응답자들은 강한 파도로 인해 해초가 휩쓸려 나가고 어린 맹그로브가 손상되었다고 진술하였다. 두 번째 환경 문제는 불법 어업이다. 바로탁 비에호 밖에서 온 일부 어부들은 2021년에 도입된 금어기 정책을 제대로 준수하지 않고 있으며(Napata et al., 2020), 불법 어구가 사용되는 사례도 빈번하다. 이에 대한 단속과 모니터링은 자원 부족으로 인해 제대로 이루어지지 않고 있으며, 고속 순찰선이 부족한 점도 문제로 지적되었다. 세 번째는 건기 동안의 담수 부족 문제이다. 이는 가정 내 기본 생활에 지장을 줄 뿐 아니라 생계 다각화에도 부정적인 영향을 미친다. 우물이 마르면 주민들은 지자체에서 물을 구매해야 하며, 해안 지역에서는 지하수의 과도한 사용으로 염수 침투가 가속화될 수 있다.

환경적 문제 외에도 두 가지 주요 정치경제적 요인이 생계 안정을 어렵게 만든다. 첫째는 편향된 토지 소유 구조이다. 바로탁 비에호에서는 일곱 가구가 대부분의 토지를 소유하고 있으며, 상당수의 소규모 어부는 토지를 전혀 보유하지 못하고 있다. 토지를 소유한 가구는 대체로 도시 기반의 부유층이며, 종종 유력자에게 토지를 매각하기도 한다. 예를 들어, 필자는 어머니가 200제곱미터의 땅을 10만 페소(약 1,800달러)에 사준 한 청년과 인터뷰를 진행한 바 있다. 필리핀의 토지 개혁은 수십 년 동안 논쟁의 대상이 되어 왔으며, 이로 인해 문제는 더욱 복잡하다.

둘째는 지역 정치에서의 대표성 부족이다. 어부들을 대변하는 정치인은 거의 없으며, 선거 기간 동안 어부들의 목소리와 요구는 농민이나 도시 유권자보다 덜 중요하게 여겨진다.

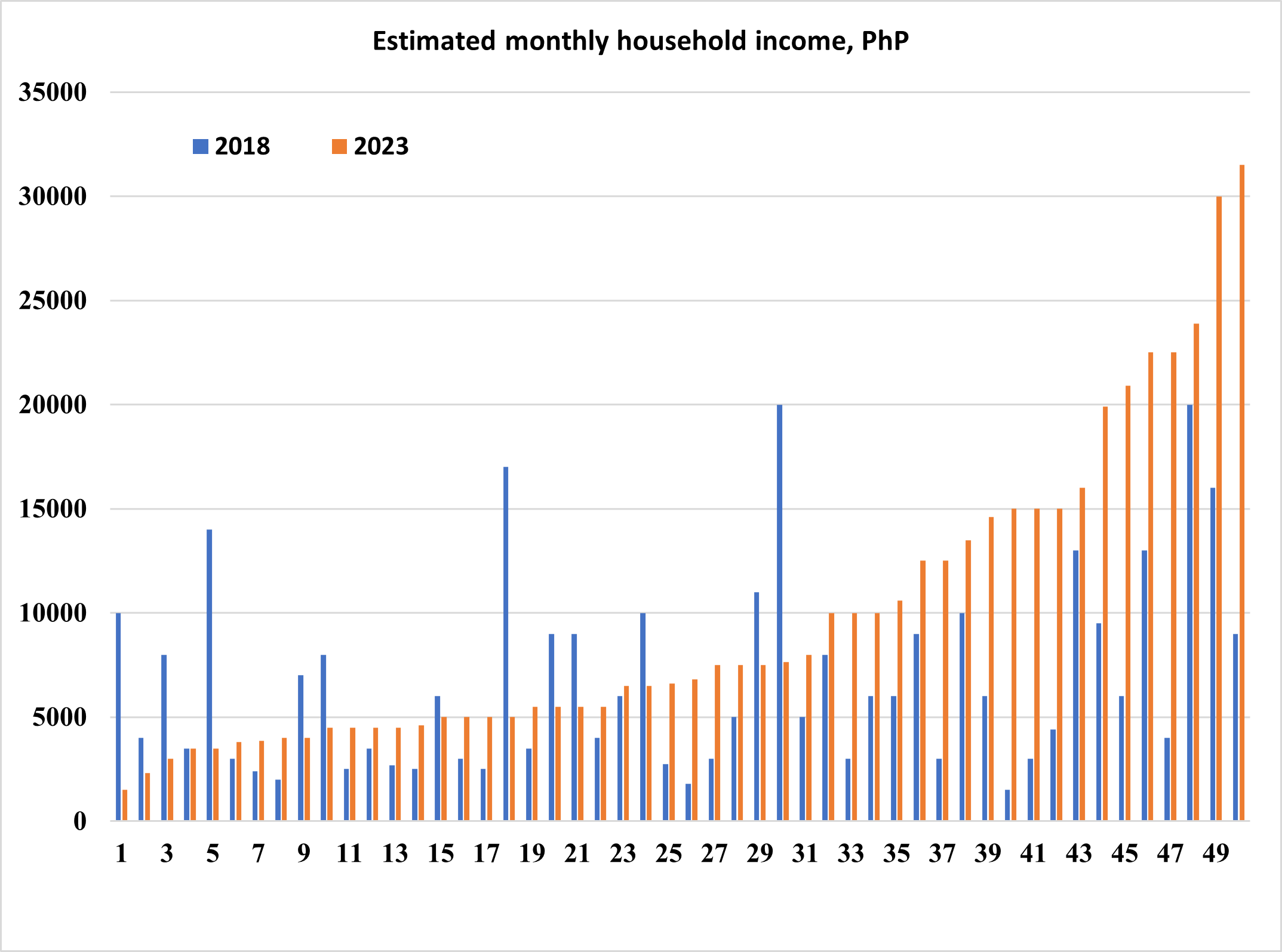

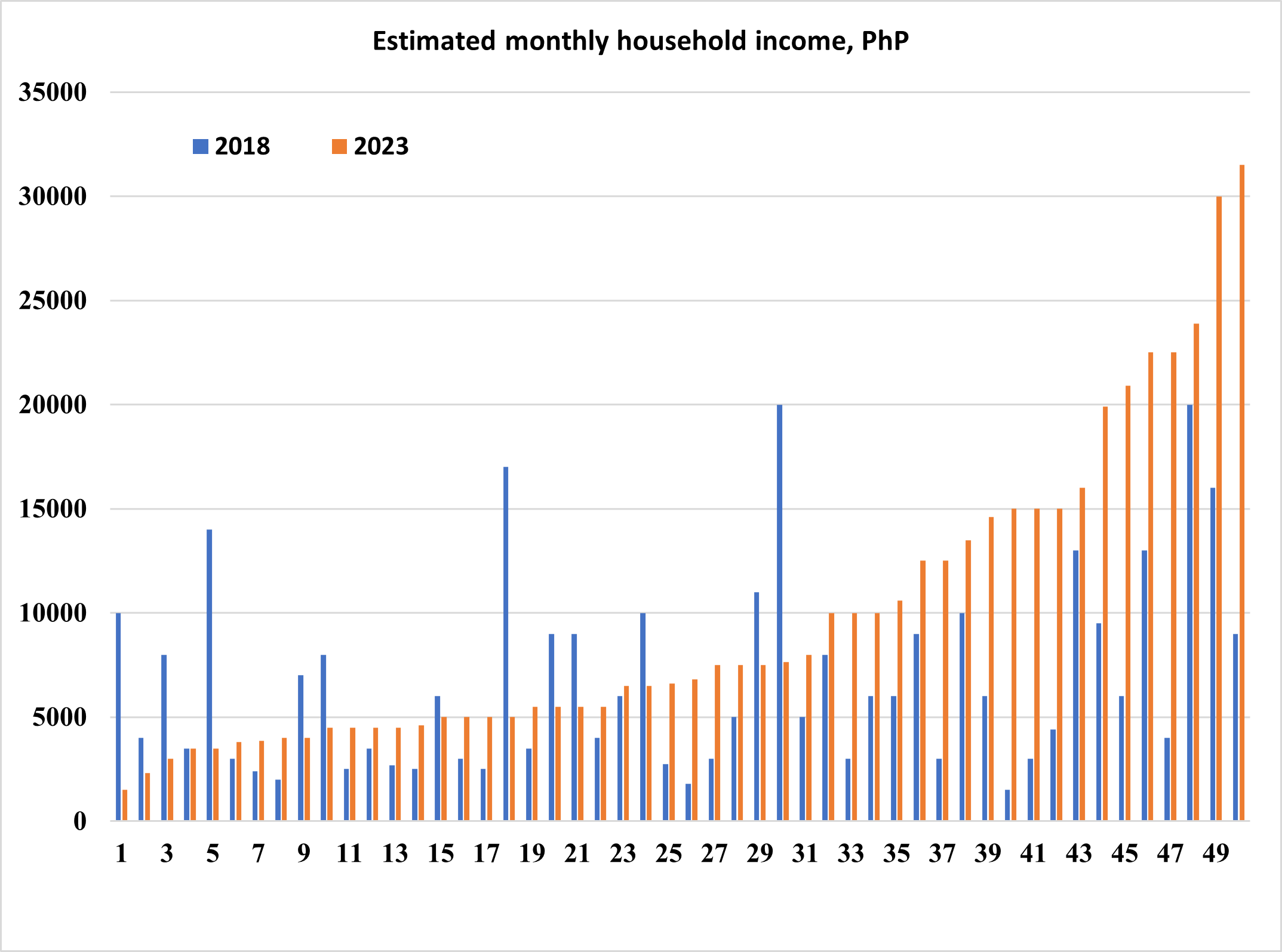

응답자의 소득 자료에 따르면, 2018년에는 조사 대상 50가구 중 42가구(84%)가 빈곤선 이하의 생활을 했으며, 2023년에도 38가구(76%)가 여전히 빈곤 상태에 있었다. 반면, 서부 비사야 전체의 가구 빈곤율은 2018년 10.1%, 2023년에는 9.8%로 나타났다. 비교적 높은 소득을 올리는 가구는 지역 내 수입원이 있거나 필리핀 대도시 및 해외에 있는 친척의 송금에 의존하고 있었다.

아래 도표는 2018년과 2023년 조사 대상자 50명의 소득 수준 변화를 보여준다. 일부 소득 증가는 있었지만, 물가 역시 큰 폭으로 상승하였다. 필리핀 통계청은 5인 가족 기준 월 빈곤선을 2018년에는 10,513페소, 2023년에는 13,801페소로 설정하였다.

어느 날, 필자와 연구 조수는 오전 6시부터 11시까지 조업을 마친 어부를 인터뷰하였다. 그는 2.5kg의 물고기를 잡아 약 400페소(8달러)어치로 팔았으며, 이 중 연료비로 80페소를 지출해 실제로는 320페소를 벌었다. 그는 “2.5kg이면 나쁘지 않은 편이지만, 요즘 식료품 가격이 너무 많이 올랐습니다. 쌀 1kg이 지금은 100페소입니다. 저축은 거의 하지 못합니다.”라고 말했다. 날씨가 좋지 않거나 파도가 높아 위험한 날에는 어획량이 적거나 아예 없을 때도 있다고 밝혔다(Andriesse, 2023). 바로탁 비에호에서 볼 수 있는 사례는 필리핀 해안 지역에서의 생계 취약성을 줄이고 실질적인 변화를 이끌어내는 일이 얼마나 복잡하고 어려운 과제인지를 여실히 보여준다.

출처: 필자가 수행한 현지조사, 2018년 및 2023년

앞으로 나아갈 길: 공정한 해안 전환을 향하여

동남아시아의 많은 취약한 해안 지역 사회를 위한 가까운 미래에는 어떤 선택지가 존재하는가? 2015년 파리기후협정(COP21) 이후, 여러 국가 정부와 국제기구는 오염과 빈곤을 유발하는 기존의 경제 성장 방식에서 벗어나, 지속가능성과 포용성, 그리고 성장을 통합하는 새로운 모델로의 공정한 전환을 어떻게 실현할 수 있을지에 대한 논의를 이어오고 있다.

지역 사회 내 가장 빈곤한 계층이 배제되지 않는 정의로운 연안 전환을 실현하기 위해서는, 해초 양식과 같은 전략이 지속적인 빈곤 감소와 고용 다각화에 어떤 잠재력을 지니는지를 비판적으로 이해할 필요가 있다. 국제노동기구(ILO)는 ‘정의로운 전환’을 “관련된 모든 이해관계자에게 최대한 공정하고 포용적인 방식으로, 양질의 일자리를 창출하고 누구도 소외되지 않는 방식으로 이루어지는 전환”으로 정의하고 있다(ILO, 2024). 그러나 필리핀에서 정의로운 연안 전환의 길을 개척하는 일은 결코 쉬운 과제가 아니었다. 필리핀은 환경 문제와 사회경제적 불균형이 얽혀 있는 구조 속에서, 이러한 전환을 가로막는 지속적인 정치적·경제적 장애에 직면해 있다. 일상적인 생계를 유지하기조차 버거운 위기 상황 속에서, 연안 지역 사회는 장기적 전환을 설계하고 추진할 역량 자체가 부족한 경우가 많으며, 중앙정부와 지방정부 간의 복잡한 관계는 포용적 접근의 실현을 더욱 어렵게 만든다. 이러한 상황에서는 정의로운 전환에 대한 국가 차원의 일률적인 청사진을 수립하기보다는, 특정 지역과 경제 부문을 중심으로 세밀하게 접근하는 것이 더욱 현실적이고 효과적이다. 연안 지역 사회에 있어 ‘공정한 전환’이란, 기후 및 환경적 도전과 지역 경제의 선택지(어업, 대체 일자리, 송금 분배), 기후 재정 기금의 접근성과 활용 가능성, 그리고 연안 가구의 역량 강화를 종합적으로 고려하는 전략을 의미한다.

Philippine coastal livelihood trajectories in need of just transitions

Abstract

This article sheds light on coastal livelihoods in the Philippines, the second largest country in Southeast Asia by population. The Philippines has a total population of approximately 114 million people; 60% of which reside in low-lying coastal areas. In addition to typhoons and storms, coastal communities are also affected by floods, saltwater intrusion, coastal erosion, sea-level rise, overfishing, and in urban areas soil subsidence. Since 2014, I have done research on coastal communities in the Philippines, particularly on how fishers and seaweed farmers cope with and respond to environmental challenges, and on how policies could become more effective. In this article I share some of my findings and the possible ways forward for policy and practice. The first case is concerned with seaweed farmers in Palawan Province, the second one with fishers in Iloilo Province. I argue that in order to achieve just coastal transitions in which the poorest sections of local societies are not left behind, it is necessary to zoom in more closely on coastal landscapes and marine-scapes. This implies careful considerations of the environmental challenges, local economic options (fishing, other jobs, allocation of remittances), climate finance, and capacity building among coastal households.

Tags: Seaweed, fisheries, typhoons, coastal governance, Southeast Asia

Edo Andriesse (Seoul National University)

Persistent environmental challenges

Pope Francis, who passed away April 21st, 2025, was a highly respected figure in the Philippines and will be remembered for a long time. This is in part because he insisted on holding a mass in Tacloban, Leyte Province January 15, despite advice to cancel the trip due to tropical storm Mekkhala (Philippine name Amang). The reason for Tacloban was to commemorate the more than 6000 people who passed away in super typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda) two years earlier.

This illustrates the impact of typhoons and tropical storms on Philippine society. According to German Watch ‘a total of 372 extreme weather events in 1993–2022 caused USD 34 billion in (inflation-adjusted) losses’ in the Philippines and the country ranks 10th in terms of countries most affected by extreme weather events (German Watch, 2025). The top four countries are Dominica, China, Honduras, and Myanmar. These events include droughts, floods, heatwaves, storms, and wildfires. German Watch also cited the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report stating that ‘it is likely that the global proportion of category 3-5 tropical cyclone [typhoon] instances and the frequency of rapid intensification events have both increased globally over the past 40 years’. It is becoming clear that climate change is fuelling the power and frequency of typhoons due to stronger winds, warmer ocean temperatures and warmer air holding more moisture culminating in heavy rainfall.

This article sheds light on coastal livelihoods in the Philippines, the second largest country in Southeast Asia by population. Indonesia has a total population of 284 million people, the Philippines 114 million; 60% of which reside in low-lying coastal areas. In addition to typhoons and storms, coastal communities are also affected by floods, saltwater intrusion, coastal erosion, sea-level rise, overfishing, and in urban areas soil subsidence (in Manila as well as in other Southeast Asia megacities like Jakarta, Bangkok, and Ho Chi Minh City)(Stockholm Environment Institute, 2024). Since 2014, I have done research on coastal communities in the Philippines, particularly on how fishers and seaweed farmers cope with and respond to environmental challenges, and on how policies could become more effective. In this article, I share some of my findings and the possible ways forward for policy and practice. The first case is concerned with seaweed farmers in Palawan Province, and the second one with fishers in Iloilo Province.

Seaweed farmers in Palawan

In the Philippines, thousands of households situated in coastal areas continue to be partly dependent on cultivating carrageenan seaweeds (most prominently Kappaphycus alvarezii); seaweeds that are refined into carrageenan, which is a thickener/binder used in food products, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical products. The country is the second largest producer of carrageenan seaweeds after Indonesia and the second largest exporter of carrageenan after China. Between 2013 and 2022 the average annual value of carrageenan exports was US$ 207 million, making it the second most valuable Philippine marine product after tuna. While Indonesia is by far the largest producer of seaweed, it does not have a strong refining capacity and exports most of its seaweed to refineries in China. Notwithstanding the well-developed and domestically integrated Philippine seaweed value chain, many households dependent on seaweeds have not managed to significantly reduce poverty and socio-economic and environmental vulnerability. Indeed, coastal communities belong to the poorest sections of Philippine society.

In my research together with Palawan State University, we zoomed in on northern Palawan Island and investigated the changing livelihoods of households cultivating seaweeds in seven villages. The island has a long history of seaweed farming. Between 2000 and 2011 production levels steadily increased and hundreds of households were able to increase their incomes and reduce the dependence on fishing. However, after 2011 seaweed production declined. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic and the December 2021 super typhoon Rai (Philippine name Odette) further hampered a return to growth. The Asian Development Bank estimated that super typhoons can reduce local economic activity by around 3% and based on historical data, typhoons cost the Philippines around $20 billion between 1990 and 2020. For example, Typhoon Kristine in 2024 caused an estimated Philippine Peso 6.20 billion in agricultural damage (Department of Science and Technology, 2024).

Source: Author

Source: Bae Gwangwon

While there has been a recent recovery, it remains to be seen whether production can bounce back to the golden years of 2008–2011. In our investigation, we focused on two questions: Why has it been difficult to maintain steady production levels and how have households sought to navigate multiple crises? Based on a 2024 survey among 138 seaweed-growing households and semi-structured interviews in 2017 and 2024, we demonstrated how households cultivating seaweeds, rather than enjoying steady increases in living standards, experience livelihoods in flux (Andriesse and Lee, 2021).

In addition to the environmental challenges, most notably dealing with the consequences of typhoons, households also need to navigate disabling local political arrangements. The following two quotes illustrate what happens when we have a closer look at the relationships between local power and financial assets:

Consolidation through associations can be difficult as some members have loans with middle-persons. For instance, one grower borrowed 20,000 PhP for the purchase of one bangka (double-outrigger dugout canoes). The lender required him to repay the loan plus interest rate within 10 months. And sometimes buyers pay growers cash advances at a predetermined seaweed price. (Interview with key informant in Barangay Babuyan, January 18, 2024)

I am also a lender. I started last year when I quit my office job. These days thirty seaweed growers borrow money from me. There is no written agreement between me and the borrowers. Some growers borrow 5000 PhP; others more, sometimes 15,000 PhP. (Interview with a President of a seaweed association, January 21, 2024)

Overall, the surveys and interviews revealed multiple challenges, including short-notice typhoon warnings; the aftermath of super typhoon Rai; ice-ice disease reducing yields; sea turtles feeding on seaweed; the lack of high-quality seedlings and fluctuating prices, and local power dynamics. Consequently, it remains hard to escape poverty permanently, and instead, coastal vulnerability is the norm. Some factors have an international dimension like climate change impacts and fluctuating prices; others have a more national and local dimension. This spatially complex set of factors has made it hard for seaweed growers in Palawan to improve their livelihoods. Between 2017 and 2024 there have been various efforts to diversify (weaving, lobster aquaculture), yet most activities eventually petered out and associations are not strong enough to facilitate transformative change. Returning to fishing and outmigration have been the most important coping strategies, putting further pressure on the marine environment and urban labour markets in the Philippines.

In sum, the results demonstrate that it is imperative to analyse livelihood trajectories involved in upstream global value chains. There is still a serious socio-economic disconnect between Philippine carrageenan exports (relatively stable and an important marine endproduct) and the thousands of seaweed growers. Therefore, coastal livelihoods remain in flux, vulnerable due to environmental challenges.

Fishers in Iloilo

Besides northern Palawan I have also done much research in Iloilo Province, located in the region called Western Visayas. In 2018 my research assistants, volunteers working for the Iloilo Red Cross, and I surveyed 313 small-scale fishers in eleven coastal villages in three municipalities (Andriesse, 2020). In 2023 we surveyed among 50 small-scale fishers in two villages in the municipality of Barotac Viejo; the same people we talked to in 2018 in this municipality. So, similar to the fieldwork in Palawan, this gave me the opportunity to add a longitudinal dimension to the research. My plan is to follow these 50 people and their families in the years ahead. Will their children be able to reach middle-class status in the coming decades? And what will be the geographical trends of working and living?

Based on the empirical fieldworks, it has become clear that environmental challenges persist, poverty reduction is a long-term process, and small-scale fishing does not culminate in higher incomes. I identify three environmental challenges and two political-economic obstacles. The first environmental challenge is adapting to typhoons. Residents of Barotac Viejo were affected by the November 7-8, 2013 super typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda), December 16-17, 2021 super typhoon Rai (Odette), severe tropical storm October 28-30, 2022 Nalgae (Paeng), and several other storms. This hampered steady socioeconomic progress as many houses and fishing boats were damaged and had to be rebuilt. New projects like diversifying into carrageenan seaweeds and planting mangroves to rehabilitate coastal areas are risky and potentially a waste of financial resources if a storm hits the area. Respondents stated that seaweeds were washed away by strong waves and young mangroves were damaged. Secondly, illegal fishing continues to be a problem. Several fishers, also from outside Barotac Viejo, do not observe the closed seasons policy, implemented in 2021 (Napata et al., 2020), sometimes illegal gear is used, and monitoring and enforcement remain suboptimal due to a lack of resources. For example, there is a lack of fast patrol boats to pursue illegal fishers. The third environmental challenge is freshwater scarcity during the dry season. This is not only a problem for existing household activities but also obstructs livelihood diversification. When the wells dry up, residents need to buy water from the municipality. And in coastal areas, excessive use of ground water can speed up saltwater intrusion.

In addition to environmental challenges there are two political-economic issues that make it hard to build more secure and stable livelihoods. The first one is skewed landownership. In coastal Barotac Viejo, seven families own much of the land and many small-scale fishers do not own any land. The landowning families are wealthy and urban based. Sometimes they sell pieces of land to those who can afford it. For instance, I talked to a young man whose mother bought a piece of 200 square meters for 100,000 pesos (approximately $ 1800). The situation is complicated as land reform has been a decades-old controversial dossier in the Philippines. The second issue is the weak political representation at the local level. Few local politicians cater to fisher folk and during election time, their voices and concerns carry less weight than those of farmers and urban-based citizens.

Based on respondents’ income estimates, 42 out of 50 households (84%) lived below the poverty line in 2018, 38 out of 50 (76%) in 2023. In contrast, the household poverty incidence for the entire Western Visayas was 10.1% in 2018 and 9.8% in 2023. Those with high incomes have either in-situ income sources or receive remittances from relatives in big cities in the Philippines or abroad. The figure below compares the income levels of the 50 respondents in 2018 and 2023. Incomes have risen, yet prices have also increased. The Philippines Statistical Agency set the poverty threshold for a family of five at 10,513 PhP in 2018, at 13,801 in 2023. One day my research assistant and I interviewed a fisher who had just returned from a 6 a.m. to 11 a.m. fishing trip. He had caught 2.5 kg of fish worth 400 PhP; around $ 8. He had spent 80 PhP on fuel, so had 320 PhP left. “2.5 kg is not bad, but food prices have risen a lot. One kilo of rice now costs 100 PhP. I save very little”. There are days when he catches less, or even nothing, when the weather is bad and the waves too dangerous (Andriesse, 2023). The case of Barotac Viejo also demonstrates how difficult it is to reduce vulnerability and bring about meaningful change in the coastal Philippines.

Source: Field survey conducted by the author, 2018 and 2023

Possible ways forward: Towards just, coastal transitions?

What are the options in the near future for the many vulnerable coastal communities in Southeast Asia? Since the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement (COP 21), government agencies in many countries and international organisations have thought about how we can achieve just transitions from polluting and immiserizing economic growth to models integrating sustainability, inclusivity, and growth.

Achieving a just coastal transition in which the poorest sections of local societies are not left behind requires a critical understanding of strategies, such as the potential of the seaweed farming for sustained poverty reduction and diversified employment. I follow the International Labour Organisation (ILO) by referring to a just transition ‘in a way that is as fair and inclusive as possible to everyone concerned, creating decent work opportunities and leaving no one behind’ (International Labour Organization, 2024). It has been challenging to embark on a path of just, coastal transitions in the Philippines. The country faces ongoing political and economic obstacles that stymie the shift towards an integration of environmental and socio-economic issues. In crisis-stricken environments where meeting daily needs is a daunting task, coastal communities often lack the capacity to think about long-term transitions and complex local-central relations hamper moves towards inclusivity. Rather than formulating national-level blueprints of just transitions it is necessary to zoom in on specific landscapes and economic sectors and investigate transition possibilities. For coastal communities, this implies careful considerations of the environmental challenges, local economic options (fishing, other jobs, allocation of remittances), opportunities related to growing funds for climate finance and capacity building among coastal households.

Author introduction

Edo Andriesse (edoandriesse@snu.ac.kr)

is a professor at Seoul National University. Edo Andriesse received his PhD at the Department of Human Geography and Spatial Planning, Utrecht University, majoring in international development studies. His major achievements include teaching human geography courses, contributing to the internationalization of higher education, and publishing several commentaries on development issues. He published many articles on coastal governance and rural development. For his latest publication: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2024.106783

저자 소개

에도 안드리세(edoandriesse@snu.ac.kr)는

서울대학교 교수다. 네덜란드 위트레흐트 대학교 인문지리학 및 공간계획학과에서 국제개발학 박사학위를 받았다. 인문지리학 교육과 고등교육의 국제화에 기여해 왔으며, 개발 문제에 대한 활발한 연구와 비판적 논평을 발표해 왔다. 해안 거버넌스와 농촌 개발 분야에서 다수의 논문을 출판한 바 있다. 최근 논문은 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2024.106783 에서 확인할 수 있다.

참고 문헌

Andriesse, Edo. 2020. “Local differentiation in diversification challenges in eleven coastal villages in Iloilo Province, Philippines.” European Journal of Development Research 32: 652-671. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-019-00233-3

Andriesse, Edo. 2023. “Could climate finance help lift fishing communities out of poverty? https://globaldev.blog/author/edo-andriesse/ (Accessed 18/May/2025)

Andriesse, Edo and Lee, Zack. 2021. “Resisting the coastal squeeze through village associations? Comparing environmental, organizational, and political challenges in Philippine seaweed growing communities.” Journal of Agrarian Change 21(3): 485-503. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12405

Department of Science and Technology. 2024. “Typhoon Kristine’s Impact on Agriculture: Crop Losses, Infrastructure Damage, and Market Disruptions”. https://ispweb.pcaarrd.dost.gov.ph/typhoon-kristines-impact-on-agriculture-crop-losses-infrastructure-damage-and-market-disruptions/ (Accessed 16/May/2025)

German Watch. 2025. “Climate Risk Index 2025. https://www.germanwatch.org/sites/default/files/2025-02/Climate%20Risk%20Index%202025.pdf

International Labour Organisation. 2024. “ILO Helpdesk: Business and a Just Transition.” www.ilo.org/resource/other/ilo-helpdesk-business-and-just-transition (Accessed 20/May/2025)

Napata, Ruby, Espectato, Liberty and Serofia, Genna. 2020. “Closed season policy in Visayan Sea, Philippines: A second look. Ocean and Coastal Management 187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105115

Stockholm Environment Institute. 2024. “The Silent Crisis of Asia-Pacific’s sinking cities”. https://www.sei.org/events/the-silent-crisis-of-asia-pacifics-sinking-cities/ (Accessed 15/May/2025)